Chasing the Moonglow at Stanford Jazz Institute

My Experience and Growth from the Jazz Vocal Program at Stanford University

Now entering the third month of my mini gap year, I feel joyful about this journey so far and optimistic for what’s coming next. This unexpected sabbatical leave due to visa reasons has granted me the luxurious freedom of traveling around the country, studying jazz music in the deep redwood forests and in New Orleans , training for marathons, and reading books for pure pleasure. It is like a summer break for elementary school kids, without the stress to prepare for any exams or job interviews. I am happy.

And this past weekend I graduated from the Vocal Program at Stanford Jazz Institute.

View of Hoover Tower from Braun Music Center, the home to the Music Department of Stanford University

On the last day of the program, we had a final masterclass on vocal techniques where we vocalists made a crying face while singing to feel how the sound differs from when we don’t move our facial muscles. It was my turn: I faked a crying face, made the sound, and simply couldn’t stop laughing.

Dena, our extraordinary vocal department faculty commented “George, you’re a person of such positive energy. We all like you.” I protested: “Dena, you know I love singing sad songs!”

We both laughed, because at that very moment, all I could really feel was only pure joy.

1 A Typical Day at Stanford Jazz Institute

The program is directed by Dena DeRose, a Grammy-nominated pianist/vocalist who has served on the faculty at Stanford Jazz for more than 25 years. She has performed at prestigious venues and festivals worldwide (Blue Note, Birdland, North Sea Jazz Festival, to name a few), and has taught at top institutions like the Manhattan School of Music and The New School in New York. She currently heads the Jazz Vocal department at the University of Music and Performing Arts in Austria.

I had 15 lovely classmates in the vocal program. The small class size allowed us to sing together more frequently and talk to each other on a deeper level. Each day began with a jazz theory class tailor-made to vocalists, followed by daily masterclasses where I could sing with a professional trio, and special presentations curated by top-notch Stanford Jazz faculty and Grammy-nominated artists. The course content covered a wide range of topics including lyrical improvisation, vocal percussion, rubato singing, band communication, phrasing, musical arrangement, and stage presence.

Students received free tickets to the Stanford Jazz Festival concerts that take place almost every single evening at the Dinkelspiel Auditorium of Stanford University. Following the concerts were jamming sessions hosted for both vocalists and instrumentalists, from 10pm all the way into the midnight (not so much a quiet night and quiet dream, lol).

We sang and played, night and day.

Dinkelspiel Auditorium, Stanford University. With vocalist peer Jeannie, and vocal department faculty Dena.

Entering this program, I carried high expectations and specific goals: to discover my unique vocal style, to be more fluent in communicating with the band, to open myself up for free improvisation, and to try out things that I don’t typically practice such as Blues and scatting. And not to my surprise, the experience was nothing but transformative.

2 Shaping My Voice through Imitation

One of the most profound and empowering lessons I took away from the program was the philosophy of “Imitate, Assimilate, Innovate”, a mantra shared by Dena.

Like many, I relied on listening to the recent cover versions of a given jazz tune instead of studying the original version that led to alternative interpretations. Dena emphasized the importance of learning the original charts and listening to the original recordings, as this allows us to better grasp the foundational elements carefully curated in the original compositions and understand the historical and cultural contexts of their creation.

At Daily Vocal Intensive Class with the professional trio led by Dena

For those of us who aren’t yet very comfortable with chart reading or ready to dive into the sophisticated jazz theory and chord progression, Dena still encourages us to learn the original compositions simply by listening.

“Believe it or not, all music can be learned by ears,” she reminded us, explaining how human ears are the most powerful device for learning music. It was quite encouraging when she affirmed for us on multiple occasions that it’s perfectly acceptable to learn by listening and replicating what we hear, as the process of imitation is the first step in almost all types of learning.

You may feel discouraged after listening to Ella Fitzgerald’s epic scatting and think “Wow, I would never be able to scat like that!”

Well, play Ella’s recording one more time. Play it 10 more times. Play it 20 more times. Play it 50 more times. Change the playback speed to 0.5x or 0.75x. Transcribe her scatting into syllables on a blank paper. Break down the rhythms and patterns into smaller chunks. Practice section by section.

If you do these, while you may still not scat like Ella, you will absolutely be able to assimilate some of her language and rhythms into your own.

And this imitation is not limited to scatting. It works well with any musical style too: blues, bossa nova, Neo-soul. Dena also encouraged us to sing along with instruments too: saxophones, drums, pianos… anything that can help us assimilate different styles, techniques, and feelings.

In the classroom, we learn from each other through imitation and assimilation too.

“Ultimately, the goal is to innovate,” Dena explained, emphasizing why imitation and assimilation not only enhance our foundational technical skills but also enrich our emotional connection to the music, making it easier to find our unique voice and vocal style in the vast landscape of jazz.

Her own journey in music is a testament to this approach. She started her career as a classically trained musician and later became a remarkable jazz musician mostly self-taught, immersing herself in the music of all jazz giants, listening deeply and practicing relentlessly, until she found her own style.

Music is a lifetime of learning,” Dena often said. Indeed, we can continue to imitate, assimilate, and innovate in music until the end of our lives because this is a lifelong journey of self-discovery and creativity.

3 Embracing Expression with Uncertainty

Entering the classroom of Dena’s “Scat Lab”, the first thing we saw on the white board was “Risk. Fail. Risk Again.”

“Risk. Fail. Risk Again.” written on the white board of Scat Lab. With vocalist friends Jeannie and Caiwei.

Fifteen vocalists gathered in a circle to improvise with the bebop classic blues tune “Billie’s Bounce” (1945) over an entire 12-bar chorus. The tempo was quite fast, and some of us were initially hesitant to put ourselves out there. I found myself constantly planning how I wanted to scat when it was my turn, but the rapid pace of the song didn’t allow for meticulous preparation.

As we began to embrace the process, we realized that seemingly unplanned and random improvisations actually carried emotional storytelling. We listened more carefully to each other, “imitating and assimilating” each other’s language, phrasing, and rhythms. Cheering for one another, we eventually built a powerful and cohesive story out of our collective improvisation.

Magic moments like this also occurred during the Vocal Percussion & Improvisation class hosted by violinist-vocalist Yilian Cañizares, where we improvised over an Afro-Cuban tune.

“We aren’t just performing. We are telling stories and expressing emotions,” Yilian emphasized. “We have to let go of our fears inside so our feelings can flow out!” Indeed, this echoed Dena’s encouragement to “risk, fail, and risk again”.

At the improvisation masterclass of violinist-vocalist Yilian Cañizares

Here are some improvisation tips and techniques that I gathered, which are equally helpful for lyrical improvisation and scatting:

Scat in response to ourselves, as if we’re having a conversation with ourselves.

Scat in response to other musicians, as if we’re having a conversation with them.

Leverage part of the previous section to be the building block for the next section, creating a call-and-response pattern.

Maintain the song form and rhythm, and improvise on the melody by changing the notes.

Maintain the song form, remove the melody entirely, improvise on the rhythm

After improvising over Bar 1–2–3–4, try Bar 4–1–2–3, Bar 3–4–1–2, and Bar 2–3–4–1 to explore new melodic patterns.

Don’t be afraid to hold a note for as long as possible for a more creatively elongated back-phrasing.

Practice omitting the last part of the phrase. For example, do not scat on the 4th bar for a 4-bar section to create a pause for ourselves and for others. Just like what we were told during the masterclass of guitarist-vocalist Camila Meza: “How to hear and listen better? By taking a pause.”

The philosophy of taking risks, embracing failures, and daring to try again both enriched my improvisational skills and taught me of the importance of spontaneity and resilience in life.

It reminded me of an insight shared by Douglas Goodkin, another great jazz teacher I met during my study trip to New Orleans earlier this summer:

“Jazz demands a kind of bravery to put yourself up on the stage and express your deepest feelings and highest thoughts, not by playing the notes already on the page, but by improvising as who you are in that moment in front of the crowd.”

Thanks to the training at Scat Lab, earlier this month I had a great time jamming “Billie’s Bounce” with Akira Tana’s Osaka Quartet [watch on YouTube], who was visiting United States from Japan to perform at Keys Jazz Bistro in San Francisco and Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City.

4 Mastering the Band’s Language

Per results of audition that took place on the first day, I was also selected to participate in the special track program called “Sing Like A Horn”, where I was assigned to an instrumental combo guided by Grammy-wining bassist Ben Williams to sing with the horn section (saxophonist) and improvise on vocal solos.

“Half Note” Jazz Combo. From left to right: Simone (guitar), Ivo (piano), me (vocal), Kevin (drum), Viggo (sax), guided under Grammy-winning bassist Ben Williams

It was in this mini ensemble environment where I learned about how a band can communicate and collaborate effectively.

Rule #1: Never come to the stage without anything to say to the band. It is always helpful to introduce the song, its key, tempo, feel, style, song form to the bandmates, no matter how confident you are that everyone may have known the song. And this is called “talking down” the band. Maybe the band wants to have some special arrangements that were not previously discussed (i.e. a “vamping”-style ending, aka a turnaround or 1–4 chords that are played over and over again until an ending is cued by vocalist or melody player). Maybe the band wants to dedicate one chorus for “trading”. Or perhaps one of the band mate wasn’t comfortable singing or playing in a specific key. Or sometimes the sequence of solo was still uncertain. So it’s always beneficial to have some prep talk.

“Share your emotions, feelings, and vision at the moment with the band, no matter how weird or heavy they may be,” Dena added, encouraging us to be completely transparent and honest with the band as vocalists, so we can curate the most authentic expressions.

Rule #2: Have a proper count-off as the vocalist. It may sound easy to just count 1,2,3 at the beginning of a performance but I learned the lesson the hard way in how to count effectively, such as counting on the 2nd and 4th beat, and not speaking to the microphone directly when counting. Ben reminded us about the “Primacy Effect” in Psychology, where the first impression created by the count-off matters as much as how we dramatically end the performance (aka “Recency Effect”).

Rule #3: Listen deeply and listen to everyone. It’s easy to play our own part and do our own solo, but it’s more artistically engaging and compelling to the audience when we are painting the story together. “Think of it as if we are in a relay race. We’re setting each other up for success. Each runner will set up the next runner in the team” Ben emphasized, stressing the importance of listening with full attention to everyone’s solo, so the story gets built up and feels like a natural conversation, instead of a loosely organized individual performance. In addition, we were advised to not to take the solo for too long. “Imagine having had an interesting and meaningful conversation with someone for 10 minutes, yet the other person keeps talking for another 3 hours non-stop. The valuable take-aways from the first 10 minutes will naturally lose their charm.”

Daily Combo Rehearsal

Rule #4: Learn proper hand gestures. I was exposed to a variety of non-verbal gestures used before, during, and after the performance. These gestures help in communicating effectively with the band without interrupting the flow of the music, allowing the band to stay cohesive and responsive to real-time changes.

Six helpful band communication gestures that I learned

Here’s a brief summary of six commonly used gestures:

Raise one finger to make a circular motion. This indicates to repeat a section of the song.

Place one hand over the top of head. This signifies that we’re going to the top (aka “beginning”) of the song, starting from the beginning, or wrapping up the solo improvisation.

Hold a fist in the air. This signals a stop or cutoff in the music, and can be used as we approach the end of the song.

Palm facing down slowly waving or moving up and down. This indicates to play or singing softer, or more slowly, reducing the volume. It is helpful when singing a ballad and when the vocalist wants to request an instrumental pause at the end of the song.

Draw a cutting line across the throat. This indicates to stop, or go to the ending. Can also be used when the soloist has soloed too long and wants to take a break.

Show 2,4,8 fingers. This requests “trading” 2, 4, 8 bars with the instrumentalist (usually the drummer).

By incorporating these elements, I felt more confident in making sure the band performance is both musically appealing and dynamically engaging.

5 The Gifts of Wisdom from the Jazz Giant

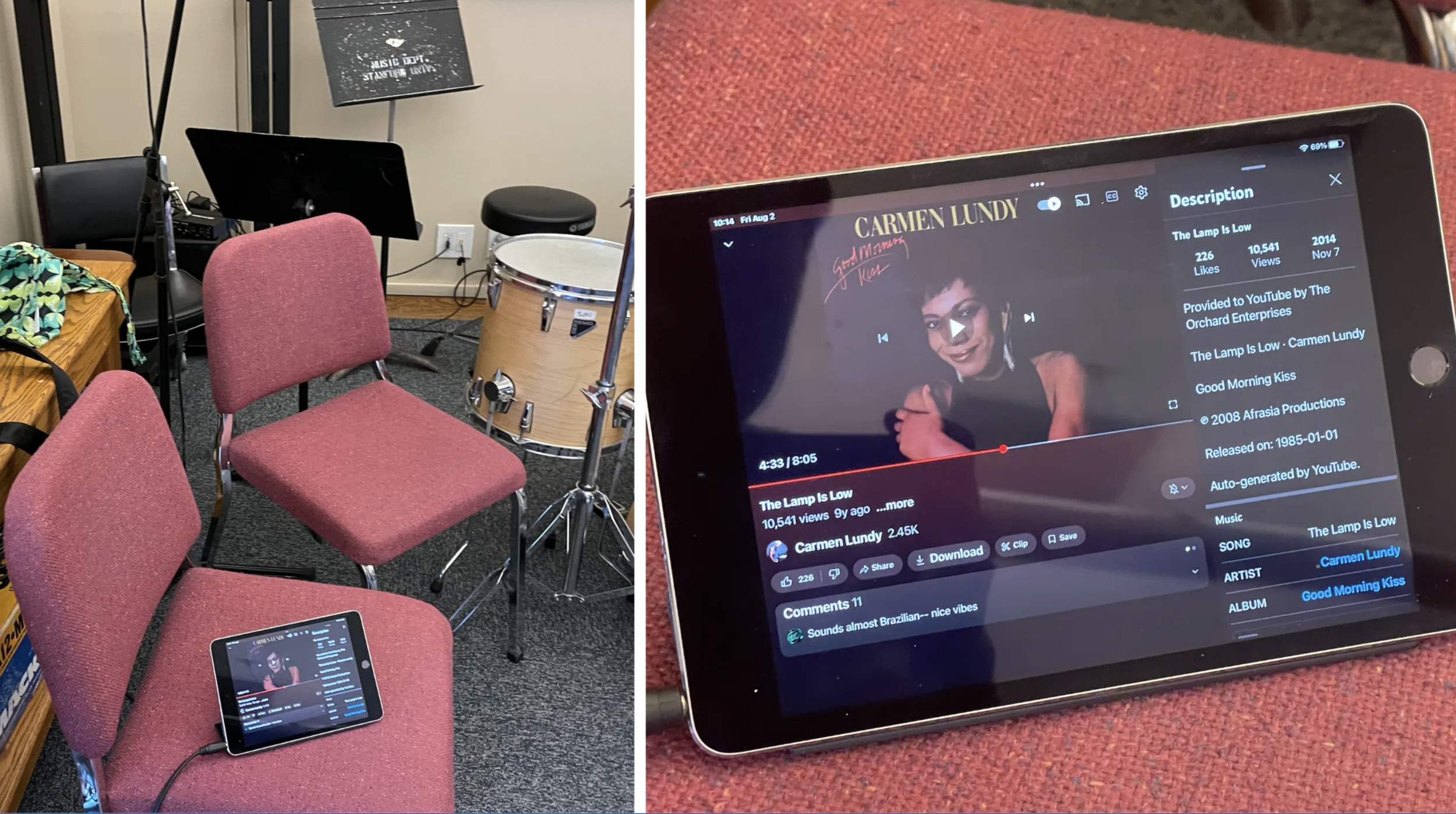

On the last day of the program, Grammy-nominated vocalist/ composer/ lyricist/ arranger/ pianist Carmen Lundy gave us a final masterclass, right before her performance at the finale concert of Stanford Jazz Festival 2024 to close the musical summer.

Carmen’s 1985 hit “The Lamp Is Low” playing in the classroom ahead of her masterclass

Carmen attended the University of Miami as an Opera major, but soon discovered that jazz was where her talent really shone. While working steadily in the Miami Jazz scene, she graduated with a degree in Studio Music and Jazz, the first-ever singer to do so. She moved to NYC in 1978, and released her first album “Good Morning Kiss” in 1985, which topped the Billboard chart for 23 weeks.

Having embarked on the performing arts journey for more than 4 decades, she has been extremely generous when it comes to sharing insights with young artists in their early career.

“Own and book our own gigs. Don’t wait for others to call and book us.” she encouraged me and the other 3 vocalist students in the classroom, “Put ourselves on the spot!” she emphasized.

At the last masterclass hosted by Carmen and Dena. With vocalist peer Dick, Jeannie, Caiwei.

She shared with us how a typical day looked like for her when she was still in college: attending classes from 8am to late afternoon, having a quick meal and getting ready for the evening music gigs, singing for 3–4 sets at jazz clubs and venues until after midnight, repeat. And she had this similar routine all the way until she graduated from the university. It may have been physically exhausting but “the sound of music showed me places I’ve never been to. It took me to so many different worlds,” she described those early years as amazingly fantastic, “and it will surely show you its magic, too.”

At the finale concert of Stanford Jazz Festival 2024, where Carmen performed and gifted me her album.

She gifted me her 2014 album “Soul to Soul” with her hand signature on it backstage of the concert. And when my vocalist-painter friend Jeannie and I asked if there were any young vocalists she’d recommend that we learn from, she encouraged us two without any hesitation: “You! You’re the ones.”

6 Resonating Beyond the Charlie Parker Memorial

The Charlie Parker Memorial Jam is an annual tradition where 200+ faculty and students gather to play the head (aka melody) of Charlie Parker’s “Now’s The Time”, then all solo at the same time at an open plaza.

The event host invited us to imagine our collaborative jamming to be an action of sending resonating frequencies into the deep space from this earth, so that their cosmic energy gets spread across the sky and echoes in the mysterious universe.

200+ faculty and students getting ready for the iconic annual Charlie Parker Memorial Jam.

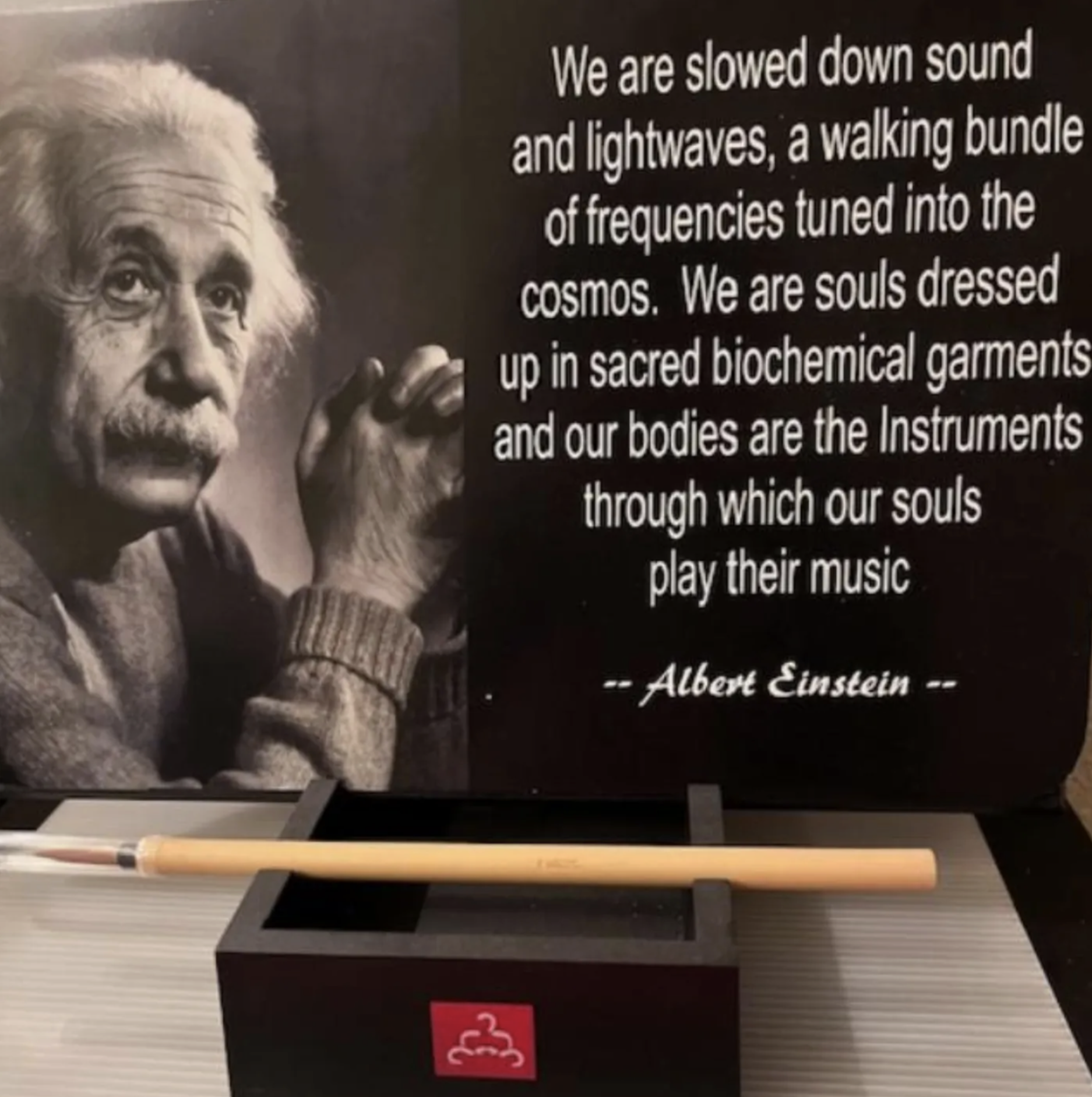

The beautifully random and seemingly chaotic few minutes reminded me the quote from Einstein about music that my friend Lawrence Wong shared with me a while ago:

“We are slowed down sound and lightwaves, a walking bundle of frequencies tuned into the cosmos. We are souls dressed up in sacred biochemical garments and our bodies are the instruments through which our souls play their music.”

Einstein’s quote shared from my great friend Lawrence Wong

Lawrence’s belief completely resonates with me, that the frequency of music resonates with the cells that make up our bodies and the cells sing and elevate us to a more spiritual level. And therefore it is through music and the arts that we glimpse a little bit of heaven.

“Immersed in music there is no time and space, just a feeling of joy and we are momentarily enlightened” Lawrence would say.

. . .

As I step away from the hallowed halls of Stanford, I carry with me more than just new performing techniques or a broader jazz vocabulary — I carry a piece of the moonglow that has been softly illuminating my path.

“We will want to treat our music as if it were a piece of poetry that we’d want to read to ourselves in the mirror every morning,” Dena reminded us,“this is how we should approach the music.”

“Also, always think about the story we want to tell to the world” singer-songwriter, Nicholas Bearde added during his vocal masterclass.

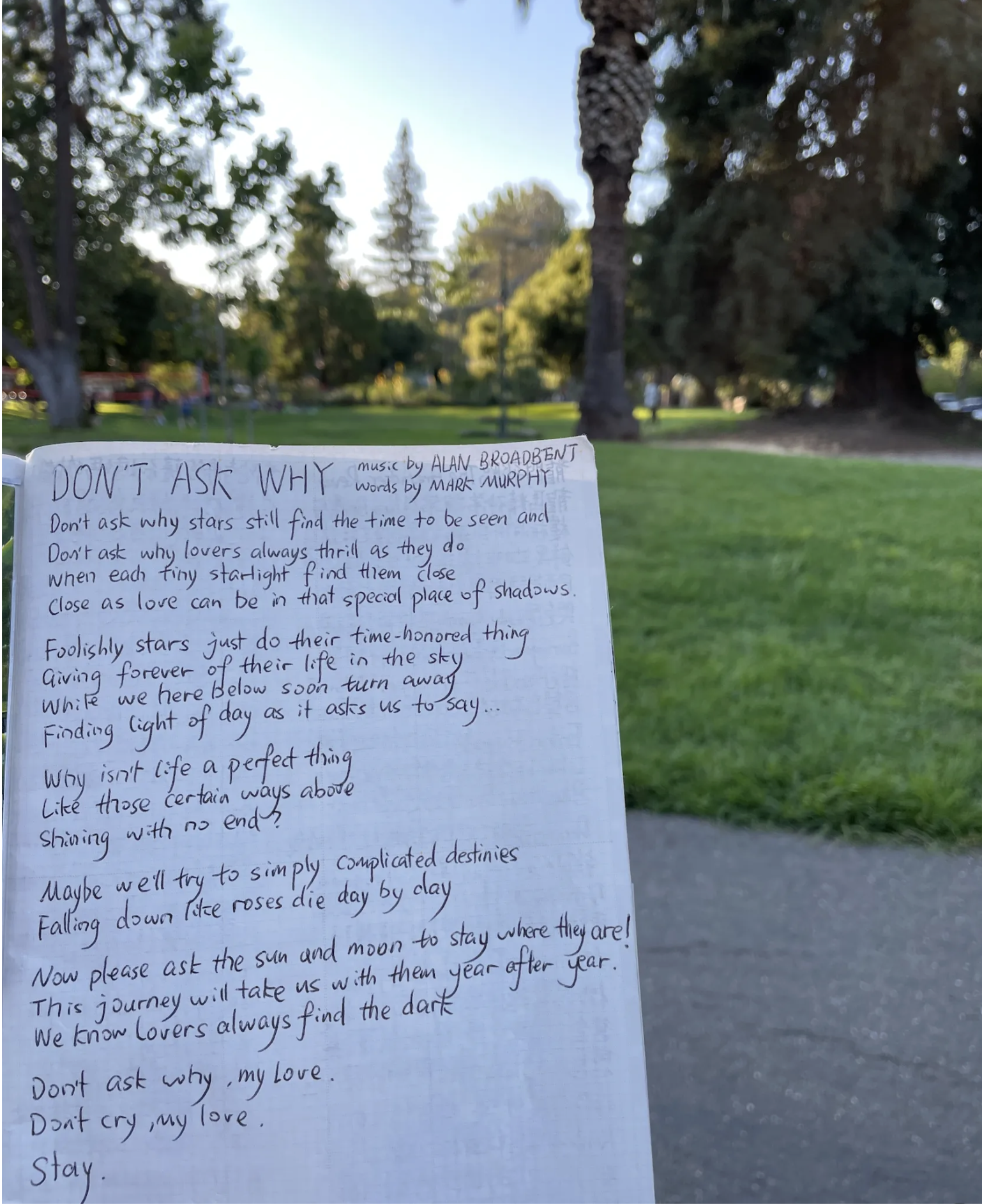

Surrounded by all my fellow musicians who treat music like poetry, I’ve come to understand that the certain sadness embedded in the melancholic songs that I love listening to (such as “Don’t Ask Why” in Dena’s 2020 album), is in truth, the twin of joy.

“Sadness is part of joy”, Dena said, and I see now that each note I sing is a step closer to the joy that I’m pursuing and hoping to share with the world — a kind of joy that, like the moon, shines brightest when it embraces both the darkness and the light.

I’ll continue to chase this moonglow, in moments of quiet introspection, and in notes that linger long after the song has ended.

. . .

A big thank you to my family of friends who always support me in my pursuit of music.

With Nicholas Bearde (left bottom), Dena (middle), and Thu Ho (right). Thu is an alumna of Stanford Jazz vocal program 8 years ago and an accomplished jazz vocalist in the Bay Area. Photo Credit (top left): Diane Battencourt

“Body and Soul” performed at Campbell Recital Hall with Half Note Jazz Combo

The colorful sky in the evening following the graduation from the program. Downtown Palo Alto, California.

Cupcake with a mini saxophone at the After Party.

Learning the lyrics of “Don’t Know Why” on a bench in Downtown Palo Alto, California.

About Honolulu Mailman

Honolulu Mailman 島嶼郵差 is a San Francisco-based Jazz vocalist on a journey in search of authentic voice and sound that inspire and then deliver those stories to the world. He has a penchant for delicate and sensual tones in the Jazz, R&B, Bossa Nova, and Neo-Soul genres. He enjoys bringing people together through organic music experience curated with notes, rhythms, melodies, and love.

Stay connected for handpicked tunes, captivating stories, and tips on performing.

Subscribe to my YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/@Honolulumailman

Follow me on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/honolulu.mailman.music/

Visit my Personal Website: https://www.honolulumailman.com/